Time to Ditch Dewey? Shelving Systems that Make Sense to Students (Learning Commons Model, Part 4)

by Heather E. Kindschy

This is Heather Kindschy’s fourth article in a series on the Learning Commons Model. Be sure to take a look at the other articles in the series.

As a participant in my school district’s pilot program for the Learning Commons Model of school libraries, I am required to track the questions we are asked by our patrons. Since our physical transformation has taken place, many of the questions were resolved, but the one question we were still hearing most often is: Where are the such-and-such books? Based on this question log, we realized that our old classification and shelving system was failing our users.

When looked at from the perspective of our youngest students, the task of finding a book is a daunting one. A five-year-old has to go to the computer and open our OPAC. Next, he has to think of the correct search terms and know how to spell them. (I typed in “planes;” why is nothing coming up?) If he manages to find a record that looks interesting, he has to locate the call number (which sometimes isn’t a number at all). He then has to write the call number down with 100% accuracy. (Don’t forget the first three letters of the author’s last name!) Finally, he has to go to the shelf to find the book. Whew! I am exhausted just typing that paragraph. I began observing our users, and I saw that this was not just a problem for our youngest students; fourth and fifth graders (and even some teachers) were struggling. After taking a hard look at the evidence, I knew that the Mt. Bethel Learning Commons needed to ditch Dewey.

Ditch Dewey? Are you nuts?

It turns out, I am not the only one who has noticed the shortcomings of the Dewey Decimal System. In their 2013 Knowledge Quest article entitled “One Size Does Not Fit All: Creating a Developmentally Appropriate Classification for Your Children’s Collection,” Kaplan et al, use the Dewey 600s or Technology section to illustrate how unintuitive it can be for children. Think about the subjects that fall here: Inventions, makes sense. Human body, okay. Electricity, yes. Robots, still on board. Cooking, wait what? Sewing, huh?! Woodworking?! To most non-librarians, these last three examples are illogical, and there are many more examples across the spectrum (Culture in 300s, but history in the 900s? Folklore in the 400s, but other literature in the 800s?), far too many for me to be comfortable with the status quo.

Ditching Dewey is a mind-boggling idea for many in the library world. The most frequent worry that I have heard is “What will happen when the students go to middle/high school or the public library and they don’t know Dewey?” I worked with high school students for years; although I am certain that their elementary and middle school media specialists spent hours, even weeks, teaching the ins and outs of Dewey, these teenagers knew little to nothing about how to find books in the library without the assistance of the librarian. Yet they still managed to find the books they wanted and needed. Humans, especially young ones, are highly adaptive. Students are plenty capable of adjusting to a new system as they need to. Consider this: Almost all of country’s college graduates have successfully made the transition from Dewey to Library of Congress classification, and most of them have meanwhile managed to purchase books from a bookstore using an entirely different classification system. As soon as they needed it, they learned the system. I did, and I’ll bet you did too.

Adopting the Learning Commons Model means building a library that works best for the users, not for the media specialist, and the Dewey Decimal System was just not working for my users. My job is to support our curriculum and get books in the hands of our teachers and students. Wouldn’t it make sense to design a system that made it easy for my patrons to find books they need in the most efficient way possible? Imagine how empowering that could be for them!

Considering the Options

Changing the classification and shelving system for a library book collection is an enormous undertaking; every book that is changed must reclassified, relabeled, and reshelved. Add to this the task of teaching students and staff to use the new system, and it becomes clear that this a change that must be carefully considered and thoroughly planned before it is begun.

In preparation for this project, I did a lot of reading (see Recommended Readings at the end of this article). I had conversations with other media specialists, listened to archived conference sessions, and attended live conference sessions regarding new library classification systems. The key message I received from all this information is that there is no easy, one-size-fits-all solution. I spoke with two media specialists in a neighboring county who had reclassified their collections, and although their schools were less than five miles apart, the new library classification systems they chose were different. Each library that has undertaken this task has done so with their unique population in mind.

During my research, I learned about several Dewey alternatives that have gained steam recently. BISAC (Book Industry Standards and Communications) was developed by the Book Industry Study Group. This system is also called “the Bookstore Model.” BISAC arranges the books by subjects; in contrast with Dewey, however, it uses words instead of call numbers. An example of a BISAC call number would be: ANIMALS SHARKS. A drawback of this model is that subjects are arranged on the shelves alphabetically. So, following this model would place Adventure next to Animals, next to Art. So while we may utilize “the call number” format of the BISAC model, the placement of unlike subjects next to each other is confusing. Other classification systems use similar groupings. Besides shelf order, often each system is a variation of how the call numbers are presented to their patrons. The C3 System uses two-letter codes while the Darien Library System’s First Five Collection uses a combination of Dewey and BISAC.

The Metis System is a thoughtful and well-designed model used in some school libraries. This system is detailed in the article mentioned above (Kaplan 2013). This system was certainly created with their users in mind. In addition to creating twenty-six categories that are represented by a letter of the alphabet, this group of forward-thinking librarians thought about their pre-readers, re-oriented spine labels for younger children, considered visually impaired patrons, and unlike BISAC, placed similar subjects adjacent to one another (e.g. Pets follows Animals). For their younger patrons, they have integrated fiction and nonfiction to help teach these users the critical skill of questioning “what they learn and how to verify those facts in trusted sources” (p. 35). This skill will be invaluable when these students are searching the Web and must quickly differentiate between fact and fiction. For middle-grade students, fiction and nonfiction are not integrated but rather adjacent. The designers’ reasoning was that genre fiction stayed together but remained near related nonfiction titles.

Our Plan

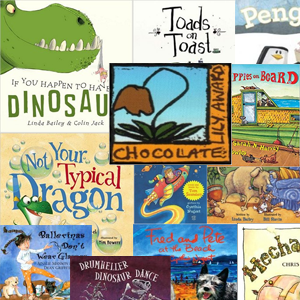

Based on what I learned, I decided to begin by reclassifying our fiction section based on genre. We often have students asking for a book in a specific genre whether it’s personal interest or for a teacher assigned project. I believe that genre-fying fiction will help our reluctant or struggling readers discover books that may otherwise remain hidden.

In order to shelve books by genre, we will need to determine the genre of each book. Some of our fiction books already have spine labels calling out their genre, but when the genre is unclear, we have a number of methods for determining it. First, we can simply look up the book in the CLCD database and check the subject headings and reviews to make determination. We can also ask students who have read it where they would look for it. Of course, we can also read the book ourselves.

We will begin tackling the fiction section when school is still in session and books are circulating. Our nonfiction section which is a much bigger beast will have to wait until summer. For our non-fiction, we will likely use a combination of the classification systems described above and develop a customized solution that works best for our users. Our system will likely be a blend of BISAC with the whole language and Metis’ thoughtful arrangement of related subjects. What is clear to me is the need for change. Recataloging and relabeling our collection will require a massive amount of work on our end, but we know that our patrons will benefit.

Truly embracing the spirit of the Learning Commons Model means figuring out the best classification system for my users. What system will empower them to find books and maybe even find the book that changes how they see or interact with the world? Students are often the media specialists’ biggest cheerleaders. If our students feel valued, other stakeholders will see the media center as a vital part of the school. Implementing a shelving system that puts books in their hands will breathe life back into our collection. Easily understood categories will save our patrons’ time and give them more opportunities to become self-directed, critical thinking consumers of information. This system will give our patrons the chance to truly embrace our motto: ASK. THINK. CREATE!

What do you think? Are Dewey’s days numbered? Let us know in the comments section below!

This is Heather Kindschy’s fourth article in a series on the Learning Commons Model. Be sure to take a look at the other articles in the series.

Works Cited

Kaplan, Tali Balas, et al. “One Size DOES NOT Fit All.” Knowledge Quest 42.2 (2013): 30-37. Academic Search Complete. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Further Readings

Buchter, Holli. “Dewey Vs Genre Throwdown.” Knowledge Quest 42.2 (2013): 48-55. Professional Development Collection. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Fister, Barbara. “The Dewey Dilemma.” Library Journal 134.16 (2009): 22-25. Literary Reference Center. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Harris, Christopher. “Library Classification 2020.” Knowledge Quest 42.2 (2013): 14-19. Academic Search Complete. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Kaplan, Tali Balas, et al. “Are Dewey’s Days Numbered?” School Library Journal 58.10 (2012): 24-28. MasterFILE Elite. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Miller, Kristie. “Ditching Dewey.” Library Media Connection 31.6 (2013): 24-26. Literary Reference Center. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Pendergrass, Devona J. “Dewey Or Don’t We?” Knowledge Quest 42.2 (2013): 56-59. Professional Development Collection. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

Thanks for the informative article! Two summers ago I reorganized our picture books into subject areas using a color-code system – it was loads of work – but very worth it! Circulation of picture books has more than doubled now that all the princess, animals, funny, school, family & friends (etc etc) picture books are shelved together. Next step is shelving fiction by genre and then I will work on non fiction – but I am still not sure how I will tackle those books! It is a helpful start that Dewey shelves subjects together (even if the order is a little confusing) – but at the very least it is time to take out the decimals.

Glad to hear your new system is working for you, and more importantly, that it was worth the work. That would be one of my primary hesitations; are the benefits enough to justify the enormous amount of labor involved? Thanks for sharing what worked for you!

Years ago, when I was a library volunteer, I was asked to make a poster that made sense of Dewey for kids. I came up with two little characters, Dewey and Decima, who ask questions or make statements about the big 10 classifications in a logical sequence of learning about the world. We start at the beginning, learn about ourselves and how we got here. We move on to learn about the people we live with, including the way our social groups operate (or don’t). We learn to communicate with other people. Then our attention turns to the wider world from the 500s on. To wit:

000: Where Do I Start?;

100: Who Am I?;

200: Who Made Me? (harvested from the Baltimore Catechism of my youth, a simple approach to religion);

300: Who Are You?;

400: What Did You Say?;

500: How Does That Happen?;

600: Let’s Work!;

700: Let’s Have Fun!;

800: Tell Me A Story.;

900: Where Do I Live? Who Lived Here Before Me?

It works very well. I’ve used it to help children as young as 6 figure out where to go to look for things, as individuals and in class groups. They really do get it.

Examples of things kids get:

-Cooking is Work, with a lot of tools and measuring, to alter plant and animal bits we find out about in the How Does That Happen section, aka Science. Tech (Work) is always related to Science, something we acknowledge with the acronym STEM.

-Art, though not always easy, pleases the maker and the audience, so it’s Fun.

-Pets Work for us and we Work to train and take care of them. Wild animals are more about How animals are, so that’s a Science thing. Tech is always related to Science.

-Folklore and fairy tales are stories we tell about ourselves and each other, so answer the “Who are you?” question, but history is a set of stories we remember about the world we live in, and Who Lived Here Before.

-A book about Mars, the planet, is about How is was formed, How it moves, How its surface is, but a book about a spacecraft to get there is a Work thing, because we have to use tools, and Tech is related to Science.

-Mars the god? He’s from an old religion people used to have, so he’s in that “Who Made Me” section, even though he didn’t make anyone.

One of my daughters, an illustrator, loved the model so much that she rendered it in an electronic format, with subdivisions by 10s under the big questions, and we print it as a flier. Children can use it easily when we use smaller words, like changing out “Prehistoric Life” for “Paleontology & Paleozoology”. Adults have also found it very helpful, even with the cute little cartoon characters.

If people want to ditch Dewey, OK, but only if it’s replaced with something that works at least as well. I find it does work, when it’s explained as a group of basic questions intended to organize knowledge rather than presented as an unexplained bunch of numbers. Generally, people have to use the tools they can understand.

Sounds like you found a way to make Dewey work for your students! Would you be willing to share your daughter’s illustration? Do you have it online somewhere?

No. Just No.

The number of things wrong with this…

Let me just start here, from the article: “I spoke with two media specialists in a neighboring county who had reclassified their collections, and although their schools were less than five miles apart, the new library classification systems they chose were different.”

Exactly! Garrrr!

And this, also from the article: “Humans, especially young ones, are highly adaptive. Students are plenty capable of adjusting to a new system as they need to.”

Precisely! They are able to learn Dewey! It’s not that hard. Uniform standards, people.

So where do you put things that cross genres, or have more than one topic? For example–Mike Lupica’s Fantasy Baseball. Is it fantasy? Is it sports? There are plenty of books that are mystery and fantasy, or adventure and mystery. If you have a book about jungle animals, across continents, Where would that go? If it’s the only book with the info needed about sloths, how is someone going to find it? It’s definitely not going to go under animals: sloths. And if they have to look it up to find it, how is that any different from using Dewey?

I think uniform standards are important; maybe more important than knowing a preschooler can look at pictures on a shelf to find a topic. After all, what are librarians for? Aren’t we supposed to be helping the kids find the items? I think a better use of time would be to help kids find the books they need, instead of watching them struggle through using the catalog when they’re too young to read.

Thanks for taking the time to join the conversation. As a teacher librarian, I see myself first as an instructional partner and resource librarian second. A new, more user-friendly system will free up me and my paraprofessional to help kids with projects and research and collaborate with teachers. For my library, Dewey simply isn’t working; I want the kids to find the books as quickly and as independently as possible. I also want them to discover books that might otherwise remain hidden to them.

As far as books that cross genres, if we can’t figure it out using CLCD or reading it, we will ask our users. They are the ones finding it, so we’ll ask them where they’d put it. No system is perfect, but Dewey isn’t working for my patrons.

I would venture to say that most libraries shelve their fiction separate from nonfiction. That is an example of deviating from Dewey. Even from libraries that do use Dewey, often the call number scheme varies dramatically. Are the biographies in a separate section or filed in 921? How many numbers past the decimal place do you take your nonfiction call numbers? Do you have a series section? Do you have a reference section that does not circulate? The point I’m trying to make is that even libraries that follow “standard Dewey,” there really isn’t a true standard out there.

This decision was not made overnight. I have spent years thinking about it and months researching better ways. I am not going to continue doing something because that’s the way it has always been done if the system is failing my users.

I believe librarians who focus on following archaic technical practices like cataloging using the DDC are marginalizing themselves and their programs. The DDC is a great classification system but not a great access system for anybody. My goal is always to connect users with information (not follow uniform standards for the sake of it)- and if I can do that by categorizing books for my students in a way that they can use seamlessly and independently – than I’m doing the right thing! We can spend more time teaching information literacy skills and preparing them for college (and the use of the Library of Congress system).